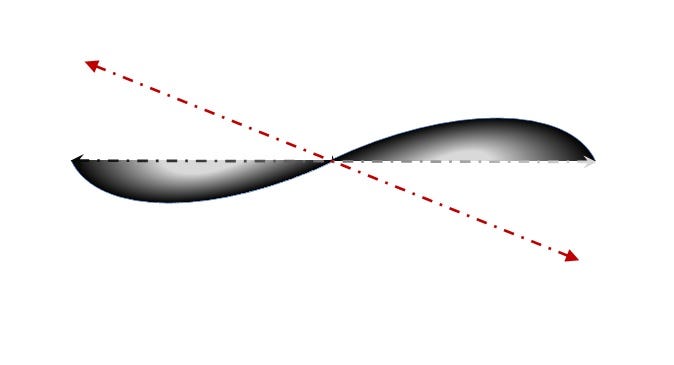

Bucket List versus Lifestyle - Dimension Analysis

Are you simply making a list and checking it (off) not even twice?

The term “bucket list” seems to have entered the lexicon around 1960, but it really didn’t take off until the early 1980s peaking in 1994. This was well before the popular 2007 movie “The Bucket List” starring Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freedman. Today it is a very commonly understood phrase.

It is also popular conceptually as a motivation for people to do things they desire to do but have not yet. This desire comes from various motivations including intrinsic desire (they really want to do this—maybe always have), obligational desire (they feel should do this including they should want to want to do this), and achievement desire (they have this as part of a bigger set of desires where it might not stand on its own—it fits into a portfolio as a nearly necessary but certainly not sufficient item by itself).

The virtuousness of these desires varies as should be obvious. To start with the desire itself might not be morally righteous. It might also suffer from being suboptimal to alternatives. For example, suppose you very much desire travel but also very much desire to leave a financial charitable legacy. Too much of one will come at the expense of the other in a way that is probably not maximizing to your overall set of desires—at the margin you should travel less once the opportunity cost of the travel (foregone charitable resources) exceeds the benefit of the travel.

Before you jump to the quick conclusion that one should not want to want something, realize that it goes both ways. Certainly, you sometimes want to want in a way that is not true to yourself or your moral compass. Wanting to be a car guy or like expensive watches when you really don’t could fit into the former description while wanting to have a lot of sexual partners (a so-called “high body count”) when you think that is morally wrong would fit into the latter.

Other times you want to want in pursuit of being a better person. This could be in a moral sense or in an achievement sense. Wanting to live one’s faith more truly for example by attending church regularly or being kinder to others would fit the former. Wanting to work harder at one’s job to be a better employee or employer and to better serve customers would fit the latter. There is a lot of depth in Adam Smith’s perhaps best quote: “Man naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of love.”

So while the bucket list should serve as a way of defining and then prioritizing one’s goals, this is not done in a single iteration. We cannot set it and forget it. To be successful we must continually evaluate what is on the list, where it is on the list, and how we are progressing with the list.

That brings us to the other side of this dimension analysis: Lifestyle. When your lifestyle naturally matches your bucket list, you don’t need the list. A lifestyle shaped by goals and aligned to your values requires monitoring, but it doesn’t need additional motivation.

Among the many ways a bucket-list strategy might be problematic is that it becomes the ends rather than the means. The method only really works if it is a motivational guide to your life—not per se the purpose of your life going forward.

It is all too easy to fall into the trap of trite box checking. I see this a lot in how people travel. While trying not to make assumptions about others’ preferences nor to substitute my own preferences for theirs when considering if they are “doing it wrong”, very often I think people travel with a check-it-off-the-list dominant focus at the expense of the travel experience they really want to have (including what they want to want to have).

“Been there, done that,” should be a reason to not repeat a perhaps regrettable experience rather than a list of proud accomplishments. I say this because the phrase is almost always used in a dismissive if not disdainful tone. It is given as a reason to not re-plow the same field rather than as an unfortunate regret. Do you see the problem? Aside from the inevitable mistaken bucket list item, one should never have a been-there-done-that attitude about their bucket list. So, if it is “been there, done that”, you’re doing it wrong when it comes to a bucket list.

Similarly, a long list of shallow things or things shallowly done is no list worth doing. In a less extreme version we could say a to-do list is only as valuable as the items on the list are themselves (individually or in total) and how they were achieved.

To be sure one could criticize me for at least running the risk of this in my Goals in the 50th Year among other choices I’ve made throughout my life. The fact I think about the risk of this (previously and particularly in writing this post) gives me comfort that I am avoiding the mistake.

There is another problem with a bucket list: It often is seen as an end-of-life catch up rather than a goals-throughout-life guide. Many things that make the list are there because one does not have the means (time or money) or wisdom (“I never realized how desirable that could be”) to accomplish them before older age. Other things make the list because one is too scared to put them there until the stakes are lower—a risk aversion that comes in many flavors. The presumption is having less to lose now, so it is safe to contemplate if not outright attempt. This is often correct—you shouldn’t take up extremely risky behavior when you have a lot of life ahead of you and/or people depending upon you.

As reasonable as any of these end-of-life listing reasons can be at first glance, I think all of this can and should be challenged or at least stress tested. Risk can easily be overstated, and when present, it can be mitigated. Further, there is no reason to believe your future (older) self will in every aspect be wiser or have superior preferences. Further still, a bucket list item recognized and achieved (or just attempted) early in life can shape and enrich one later in life opening up wisdom and values otherwise foregone.

There is also the problem of putting items on the list rather than attempting them. Writing them down as a goal isn’t the same as achieving the goal. Think of this as the logical extreme of the shallowly done problem mentioned above. This should be obvious, but it is often not. Intentions are not achievement, and intentions without action is a form of self deception or explicit, outward lie.

This problem is exacerbated with a circular justification of “I couldn’t do it then, but I want to do it now, but I can’t do it any longer, so the list is all I’ve got”.

A bucket list isn’t a first, best solution. It is a life hack. Life hacks are imperfect but useful, but they risk being distracting. More importantly they risk missing the forest for the trees and the road less traveled. When the goal is simply the destination, a true short cut is best. When the goal includes or simply is the journey, the short cut is a failure.

The more your lifestyle is crafted and refined to match your ever-changing desires, the less you need a bucket list. Perhaps the bucket listing is the start of the process or the periodic review of where one stands—a check up on lifestyle.

Remember that unless you are deeply irrational or terribly mistaken, what you actually choose to do is what you actually value. If a bucket list is the best way to correct these errors, then use a bucket list. But do not let a bucket list actually lead you down a path of irrational or mistaken pursuit. Have this single item on your ultimate and perennial bucket list: Have a lifestyle that eliminates the need for having a bucket list.