In Defense of "It Depends"

When the right and best answer is mocked.

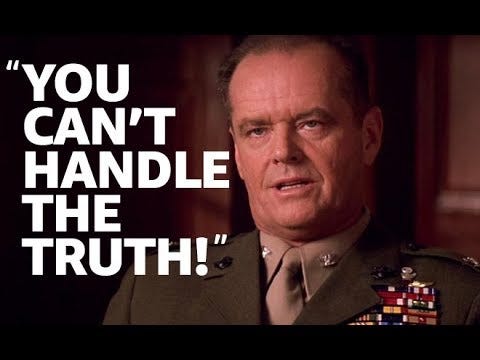

I am going to try to avoid being snarky or simply dismissive. I also don’t want to fall victim to taking literally something said more in jest. At the same time if you don’t understand and appreciate that the right answer is “it depends” to some degree for all important questions, I don’t know how you sleep at night.

Perhaps I do know how you sleep at night: in blissful ignorance comforted by the blanket of poorly reasoned beliefs. So much for my aspirations in the first paragraph . . .

Let’s start again . . .

In my work as a financial advisor my colleagues and I begin many an answer literally or in not so many words with “it depends”. We use it to express an important point, but it gets twisted upon us as if it is a reluctance to take a stand or tell the truth. In fact it is the truth. We use it because making a definitive statement would be a lie.

Human nature causes us to HATE this. We don’t just want answers. We want answers we can take to the bank. When it comes to the big questions, the ones for which we can’t help but get emotional, we yearn for a definitive guidepost we can have every confidence in.

Unfortunately, answers to questions like this almost never exist. And what is crazy is everyone knows this. It is no surprise at all, but still no one accepts it at the same time.

Consider types of questions along a spectrum—from the uninteresting/obvious to the highly interesting/mysterious.

Some examples along this dimension:

Will the sun rise tomorrow?

Will it rain here tomorrow?

Will it rain here two weeks from today?

Will a rain-wrapped tornado threaten my house next May on a day that I am at home?

Only interesting questions can have interesting answers short of creative license, which is tantamount to rewriting the question. I can give a creative answer to an inquiry about the sun rising tomorrow, but what I would probably be doing is taking you along a metaphysical journey that might require a dose of psilocybin.

For questions that are interesting, answers can be speculative or conditional or both. A speculative answer is fine as far as it goes, but it is given under false pretenses if it isn’t disclaimed as such. That is where I find the most problem with how many in my industry and many in so many realms offer answers. Sometimes this is unintentional miscommunication—what I thought was an obvious point of conjecture you interpreted as concrete fact. Sometimes this is intentional obfuscation—aka, a lie.

Conditional answers run the risk of the proverbial eyeroll and reference to the adage about one-handed economists. Yet that’s the good stuff.

Will stocks outperform bonds over the next 12 months? I might begin to answer this with a question (another underappreciated but nevertheless important facet of good answers, but that is for another post)—What do you mean by “outperform”? More to the point of this post, “Well . . . [ID] here are the conditions that might lead to stocks>bonds . . . here are the counter scenarios . . . let’s consider probabilities with these . . . excuse me, sir, you seem to have drifted off to sleep . . .”

The interesting answers are interesting not because they give a definitive answer but rather because they help define the understanding of the question and what an answer to it would be if it were an uninteresting question.

A coming recession of X magnitude lasting Y number of days associated with outcomes [A through E] is an answer either highly speculative or ridiculously absurd depending on your point of view. Yet that answer goes from bad to meaningful once we define what it would take to get to where that answer is obvious—the conditions that might bring it about.

Don’t look for definitive answers to difficult questions. Look for great reasoning with appropriate skepticism that actually leaves you still asking the original question just now with a better framework.