Just Give Me The Best Rate

How hard can it be?

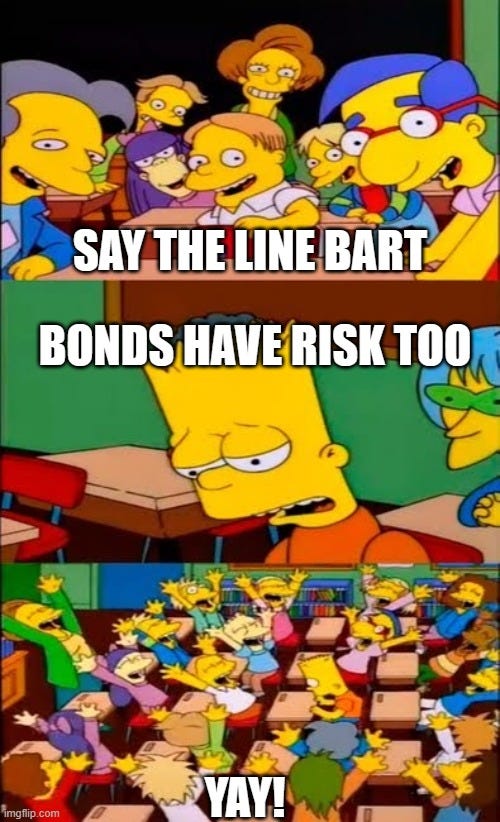

Although exaggerated here for effect, the best advisor is not one who simply gives you want you want. The best advisor helps you understand what you want, guide you passed what you want to avoid, and navigate the tradeoffs.

Investor: “I would like to invest some money, about $100,000. But I don’t want any more stocks—don’t need that riskiness. So I’m thinking bonds, which I know is all about the interest rate. So please invest me getting THE highest rate.”

Advisor: “Okay, I see a 20-year bond in Dryhole Energy, Inc. with a yield to maturity of 28%. But are you sure you want to take that much risk? There is a decent chance they default on the loan.”

I: No, I don’t want to take any risk. That’s why I’m looking at bonds not stocks!

A: Well, there is always risk. So you want less risk than that. Would you want to diversify that risk some by getting a portfolio of high-yield bonds (AKA, junk bonds)?

I: That doesn’t sound like less risk.

A: Well, it is a lot less than an issue from a single company. Plus it will be shorter in term—so less duration (AKA, interest rate risk). There is a fund yielding about 8% with an average maturity of about 5 years (duration of 3.25).

I: Five years sounds good. How would you describe its risk.

A: It is basically as risky as stocks.

I: [getting irritated] I told you NO STOCKS!

A: Well, technically it is not stock. But you have a good point. I was just circling around a bit to make sure you knew the highest rate might not meet your other conditions and desires.

I: Thanks for the trip down Passive Aggressive Lane. Now, back to business. What BOND THAT IS LIKE A BOND rate can you get me.

A: There are quite a few individual investment grade corporate bonds we could select.

I: Great, let’s do that.

A: Don’t you want to know about the risk?

I: [dejected] Yes, please, tell me the risk.

A: Well, individual corporate bonds still have small but meaningful default risk. And their risk profiles change over the life of the bond (for example, the duration will change). Plus your small purchase comes with an additional transaction cost.

I: So, a bond fund?

A: A corporate bond fund would greatly reduce these problems. It would still have risk from default, but that is quite minimal. The biggest risk is that in something like a severe recession there could easily be a strong drawdown in the value of the bonds. And there would always be some interest rate (duration) risk.

I: So when my stocks go down my bonds might go down too?!?

A: Yes, potentially and initially at least. The corporate bond fund probably falls less and recovers sooner depending on the nature of the economic downturn. Can I ask a question?

I: You just did.

A: Is there anything specific you are thinking about with regard to this bond investment?

I: Thank you for asking. Yes, in about 5 years I will need to pay off a balloon loan due on my boat, which will be about $70k, plus around then my son will start college. Depending on scholarships I might need to help him out a bit.

A: Oh, well in that case I would strongly recommend against the bond fund. Even a govt/credit fund that has a large proportion of U.S. Treasuries wouldn’t match up well for your need given the duration risk.

I: You keep using that word, remind me what that means.

A: Duration is the measure of interest rate risk. Put simply it is the amount your bond or bond fund decreases (increases) in value when market interest rates increase (decrease).

I: Why would my bond value go down if interest rates go up? Aren’t I locked in at that rate.

A: Precisely because you are locked in does the value change. Why would someone buy your 4% bond from you if they could get 5% in the open market? The only way they would is if you offered them a discount (AKA, lower price therefore lower market value).

I: I see. Well, what can I do?

A: A 5-year U.S. Treasury is yielding 3.75%. We could lock that in today. And of course there is no risk of default like with the corporate bonds.

I: Ha, I’ve heard what you’ve said about the U.S. debt situation. Sounds like default risk to me.

A: Well, the U.S. government can always make us pay more taxes to pay off that debt including the bond you’d be purchasing. If that fails, they print the money that is used to pay you as well. So, yeah, there is inflation risk, but not probably default risk in a technical sense. Still, VERY little chance of a problem like that in the next 5 years. And even if it did happen, you’d have . . . let’s say “other problems” to worry about.

I: Okay, that aside. 3.75% is the highest rate on a UST?

A: No, not even close. A 2-year is yielding 4.05%, a 1-year 4.48%. In fact every term shorter than a 5-year is yielding more. A 3-month is at 5.21%.

I: [flabbergasted] Then why would you stick me with the lowest rate?!?

A: Because it is very likely the best rate considering how it matches up with your liability—removing duration risk.

I: Why might it be the best rate? Last time I looked 5.21 > 3.75.

A: Think about why people in the market would settle for 3.75% if they could get more for shorter. What do they have to do after the 3-month matures?

I: Reinvest in another UST, but they then could pick between another 3-month or any other as long as 4.75 years. Sounds like option value.

A: Yes, there would be some option value, but that has upside and downside. The market is saying pretty strongly that the likely path of interest rates is downward. That is why they would settle for 3.75% for five years—they expect rates to fall even lower than that over the course of the five years making the effective rate over that period lower than 3.75%. Therefore, 3.75% looks like the best rate given your timeline.

I: So the 5-year rate is the highest rate from there on out?

A: Actually, no. The 10-year is 3.88% and the 30-year is 4.14%.

I: Then why don’t we get those? Seems like they are going to go up in value if the market’s rate prediction plays out. You see, there is this thing called duration risk . . .

A: That’s a big “IF”. Rates overall or just for those terms could go up over the next five years. Inflation might unexpectedly rise again or investors might start pricing in long-term difficulty for the U.S. Treasury. Those are just two pessimistic reasons. But also long-term economic growth might improve strongly, which would also have an increasing effect on rates. Anything that raises rates upward would impact significantly and negatively those long-term bonds more than short-term bonds. Since we’d have to sell them at some point in the next five years, we might be looking at a very sharp haircut. Maybe something that resembled a stock market-type loss.

I: Okay, so a 5-year UST it is. Glad we got that settled. It will be nice when it matures and I can look back knowing I did the best thing and made the most money [I should have reasonably expected to make given the risk].

A: Can I record you saying that?

I: [suspiciously] Why?

A: Because there is almost no way you’ll remember it that way. We are finding a middle ground on risk and then finding the best return for that blend of risk. It is a certainty that something would have been better in retrospect. Maybe most of the ideas we moved away from today would have been better. Stocks might do great. High-yield bonds might deliver on those high rates. Corporate bonds the same. Yields will either be noticeably higher or lower than what the yield curve today suggests—they simply won’t exactly match it. That means you could always find a reason to be disappointed as we chose against the one that worked better (short term if rates stay high or move higher; long term if rates go lower).

I: But I’m not like that. I’m a very reasonable investor.

A: Yeah, I hear that from a lot of folks.