Links 2023-12-18 - It Ain't What You Know...

It's what you think you know that ain't so.

I think it seems to many that I go through life at times as a walking, talking “well, actually…” always looking for ways to tell people they are wrong. I promise this is not my aim. Still, it happens to be that some of the things I know a lot about (economics in particular) are things people tend to both not know a lot about and still want to speculate, pontificate, and otherwise bloviate upon.

Since I choose honesty over pleasantry with a goal of pleasant honesty, I keep swing at nearly every pitch. All of these links are in that theme.

Scott Sumner hits it right on the nose with his post Economics is Really Hard. Drawing a distinction with physics and using the example of price gouging he writes:

A science writer can tell me that quantum mechanics is true because of blah, blah, blah, but it won’t sink in. I can explain to the man on the street why price gouging is actually a good thing, but my explanation won’t sink in. It requires too much background information. Here’s just a portion of what you need to know—and I mean really know in your bones:

1. Supply and demand elasticities are far greater than common sense suggests.

2. Public policy is a repeat game—policies need to be evaluated as a long run regime, not as an ad hoc decision.

3. Retailing is a highly competitive industry, with zero economic profits in the long run.

4. Willingness to pay is far less correlated with wealth than you might assume.

5. Price controls are not an effective way to redistribute income.

6. The economy is not a zero sum game.

Amy Crockett understands something that many, many people do not about this year’s version of blame-the-corporation: namely, Taylor Swift (not Ticketmaster/Live Nation) is the monopolist, she and her fans have the market power, and service fees are a benefit to buyers. As she writes:

In fact, artists including Taylor Swift, price “below market” to try to make their concerts accessible to all fans. Pre-sales and verified fans are systems put in place to try to get tickets into the hands of actual fans planning to attend the concert and not scalpers. But selling concert tickets at below the market value creates other problems. We have established that demand far exceeds supply. There has to be some way to allocate this scarce resource. One way is allowing prices to dictate who values them the most monetarily, one is to have a verified fan process and lottery system. But whatever the system, some set of fans will be disappointed in not being able to buy tickets.

Perhaps we can have the government come in and allow other sellers to sell tickets. The government can create competition in the selling of tickets. But what makes us think multiple sellers would make the market any different? If I know I am selling a ticket to a unique event with excess demand, I would have no incentive to try and undercut my competitor because I know the tickets will sell regardless.

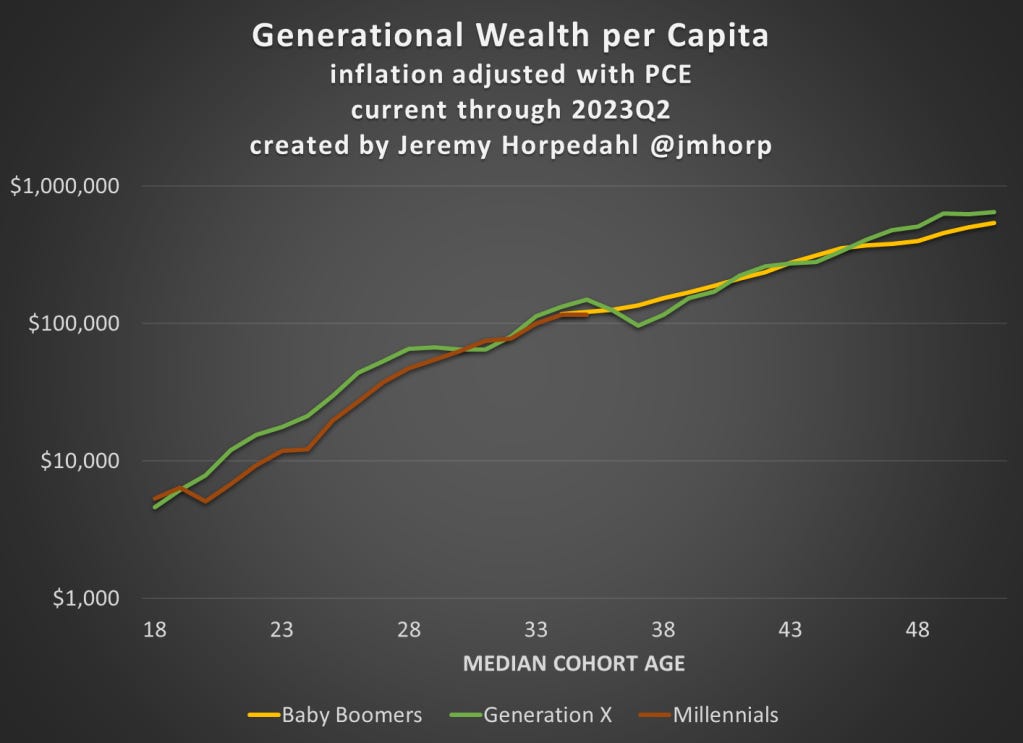

Jeremy Horpedahl cuts through a lot of the myths about wealth, income, and inflation on a regular basis. Right in line with that is this post on generational wealth. The key takeaway is that contra conventional wisdom Millennials are basically trending right along with where both Baby Boomers and Generation X charted for their first 35 years (measured at their median age).

Phillip Magness touches upon something I noticed way back in high school when the history I was learning in class was not matching up with the economics I was learning outside of school on my own. In his post he shows how college history textbooks are spreading misinformation about the Great Depression. A slice:

Turning to the nine most-common US history textbooks, we found a very different story. Monetary explanations of the Great Depression were seldom mentioned at all. Only two of the nine texts mentioned the role of Federal Reserve policies. The protectionist policies of Smoot-Hawley were largely omitted. US history textbooks even neglected doctrinaire Keynesian explanations rooted in an aggregate demand contraction.

Instead, all nine history textbooks attributed the Great Depression to a class of explanations known as “underconsumption” theory. Briefly summarized, underconsumption holds that economic production outpaced what most consumers could purchase given their low pay, triggering a contractionary event in the form of the Depression. This argument attained popularity in the early 1930s, and was used to justify many of the economic planning and regulatory programs of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Economists today overwhelmingly reject “underconsumption” theory. Even Keynes expressed skepticism of the notion, and attempted to prod the Roosevelt administration over to an aggregate-demand-based theory of the unfolding events. For the past 80 years, few if any economists have seriously entertained “underconsumption” as a viable explanation of the Great Depression.

Jeffrey Singer knows that despite the desires of prohibitionists to stop e-cigarettes from offering flavored vapes the effort was doomed to failure due to the iron law of prohibition. The result is both added potency and a black market. Succinctly:

The failure of e‑cigarette prohibition was predictable—as is the advent of more potent and puff‐packed forms of nicotine vapes now sold on the black market. Though prohibitionists never seem to learn, the “iron law of prohibition” is inescapable. A variant of what economists call the “Alchian‐Allen Effect,” put simply, the iron law states, “the harder the law enforcement, the harder the drug.”

Too many people (and politicians catering to them) practice what I would call desire-based economics. It is a variant of social-desirability bias. As difficult as it is, the cure/treatment is deep thinking along the lines of challenging one’s priors and instincts.