There is no better time to travel by commercial flight than the time we live in today. For some that may seem obvious but with reservations [wink]. For others it will be less apparent as they will think back to a fictional past where nostalgia is warping their perspective. In truth this is a golden era where the only concerns are that it isn’t as good as it could be, the rate of progress is slowing drastically, and reliability has taken a hit.

As Tony Morley writes,

If you had to choose a moment in history to take a commercial flight between any two major cities on earth, and you didn’t know in advance which flight, which airline, or which budget or class you’d be flying — to paraphrase Barack Obama in a 2016 address, “You wouldn’t choose the fifties, or the sixties, or the seventies. You’d choose right now.”

That is from his piece at The Up Wing, where he details how air travel is safer, cheaper, and faster; goes farther; and is more equitable than at any time in history. And this achievement gap is by a very big margin. Certainly here the magnitude matters.

I encourage you to read the entire piece. Some of the stats are stunning such as how:

Globally, between 1970 and 2021, the number of fatal airliner accidents per million commercial flights fell from 6.4 fatalities per million flights to just 0.46. Put another way, the global airline industry flew nearly 210,000 passengers safely, for every tragic life lost flying in 1970. However, by 2021, that figure had climbed to 18.5 million passengers flown safely for each life lost; an increase in the number of people flown safely per life loss of 8,700%.

As for aesthetics he writes,

Everything about the modern flying experience is more comfortable than that of the 1950s, 1970s or 1980s equivalent, at every fare price point, no exceptions. For starters, there were the aircraft themselves. Flying through much of the 20th century, presuming you could afford the privilege, was a loud, turbulent, rattling, poorly pressurised, smoke-filled, boring saga with only a magazine or book for entertainment. Many of the innovations we take for granted flying today were hard-won technological breakthroughs, regulations and standards improvements that took decades to become widely available.

When it comes to the comforts of flying, our own hedonic treadmill has helped us forget just how much more comfortable the entire experience of flying today is compared with the recent past. Enter a large modern international airport today, and you’re entering an entertainment park filled with shops, restaurants, bars, convenience stores, and lounges. These modern airports bear, with a few exceptions, little resemblance to the airports of a decade past. Modern climate control, high-speed internet access, significantly improved entertainment, shopping, gate departure displays, food options, and artwork make for a much more enjoyable wait, when compared to the past.

For all the bad press today’s aircraft get for being cramped and uncomfortable, with airlines supposedly squeezing out every dollar from passengers by shrinking amenities and space, the aircraft themselves are so much better, it’s simply astonishing. Modern aircraft fly higher, smoother, and have improved cabin pressure, air conditioning and noise insulation, dramatically reducing fatigue and pressure-related discomfort, have improved radar and navigation systems to better avoid turbulence, and are frequently equipped with entertainment systems, high-speed satellite Wi-Fi and flight tracking, unimaginable to those flying in the primitive days of the eighties, nineties and early 2000s. And all of that is to say nothing of the improved food, drink, toilets, amenities, ambient lighting, and the ability to head to the back of the plane and stretch, in a spacious common area. And all the aforementioned is available in economy; it’s obviously much better in business or first class, assuming you can and are willing to pay significantly more. With all that being said, I’d argue that I’d rather fly a 20-hour Sydney to London route today than any 15-hour flight between any two locations circa 1980, and I’d bet you would too.

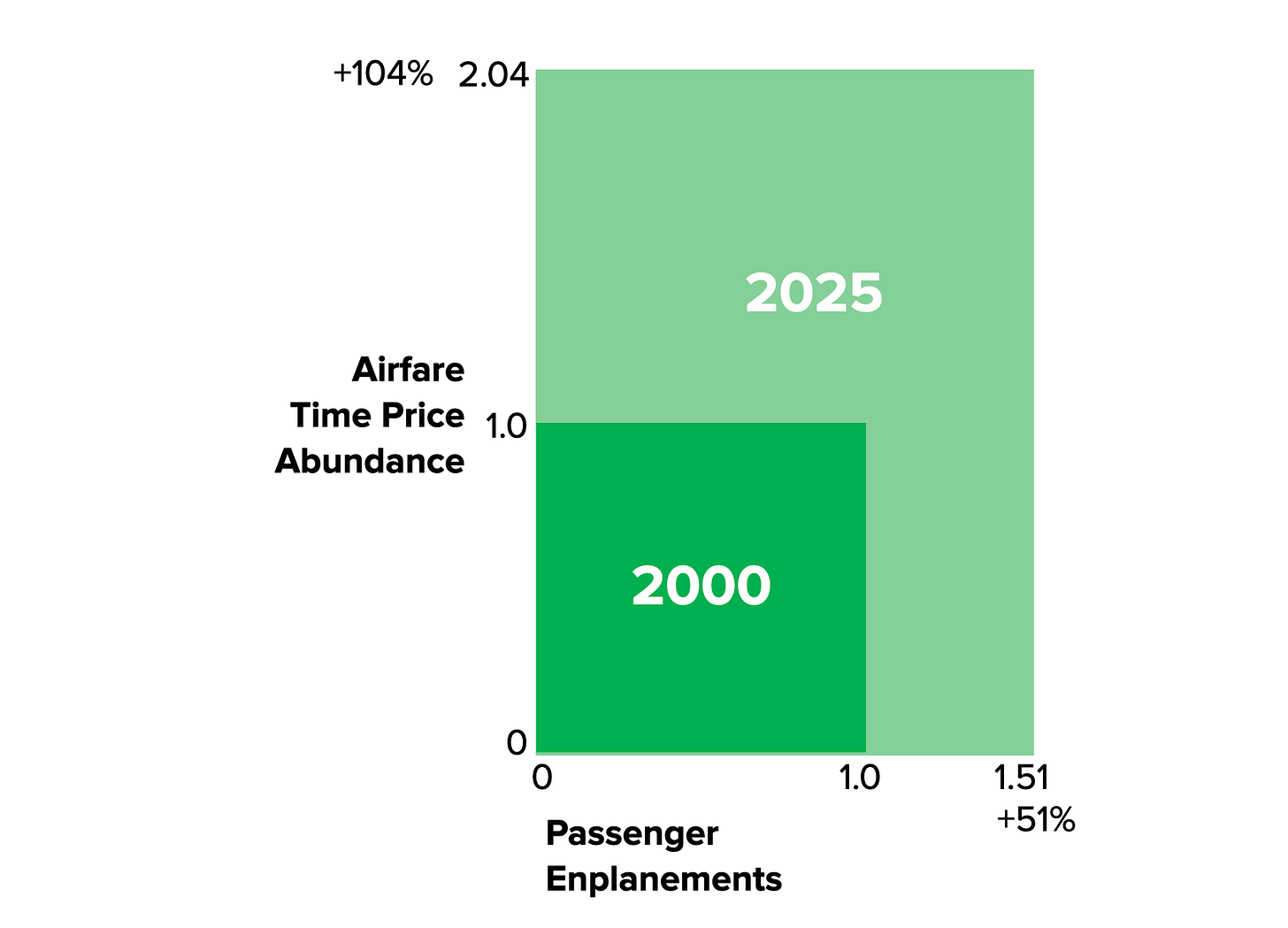

When it gets to the economics of flight, he draws upon Gale Pooley for which I’ll go straight to the source referencing his post The More We Fly The Cheaper It Gets.

Using 2000 as our baseline (setting both variables to 1.0), the initial box measures 1.0 × 1.0 = 1.0. By 2025, enplanements had grown 51 percent (to 1.51) while airfare abundance increased by 104 percent (to 2.04). The 2025 box therefore measures 1.51 × 2.04 = 3.08. Going from a 2000 box size of 1.0 to a box size of 3.08 is a 208 percent increase in total airfare abundance over 25 years, equivalent to a compound annual growth rate of 4.6 percent. At this pace, airfare abundance doubles approximately every 16 years.

We also note that every one percent increase in population corresponded with a 9.45 percent increase (208 ÷ 22) in personal airfare abundance.

As I alluded to at the top, better than ever is not equivalent to utopia. Airports in particular leave a lot to be desired—and who owns and operates airports in the United States? . . .

(For an aside on how security can be better, see this post by David Henderson about alternatives to TSA currently in operation at airports like SFO.)

Flight delays in particular deserve some attention including how the airline industry is manipulating statistics to appear better than they actually are performing. To this end, Maxwell Tabarrok explores some arguments considering if air travel is getting worse.

His post pushes back against the Morley link above, which claims (with evidence and good arguments) that air travel is all around better than ever. Importantly Tabarrok’s is not at all a complete refutation, but it does show that there is nuance to be considered.

Delays are one such area:

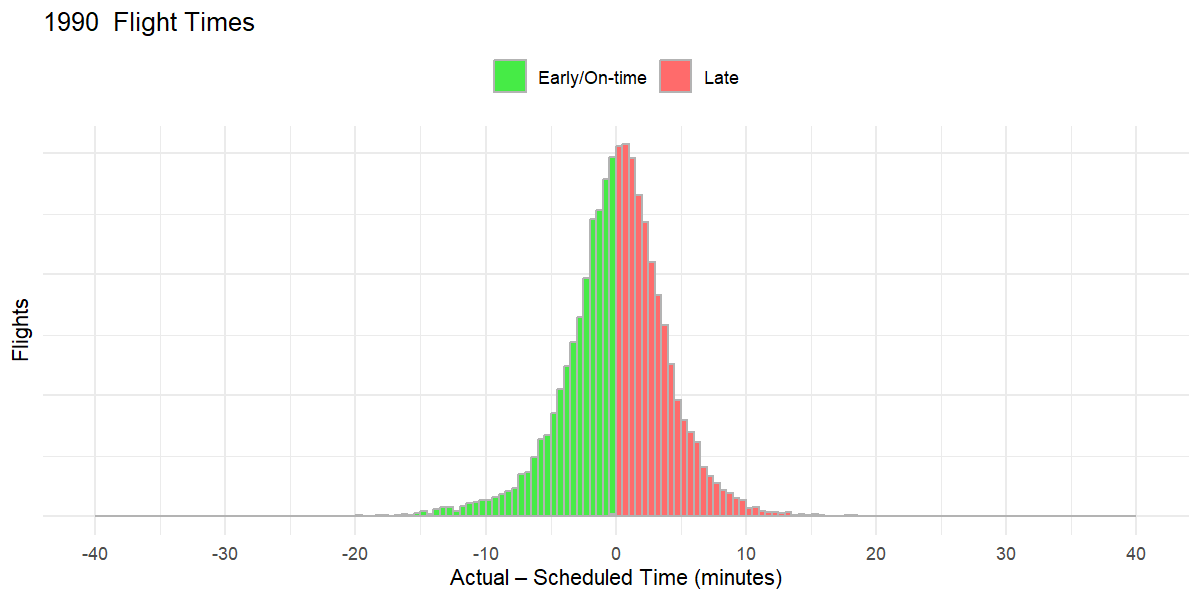

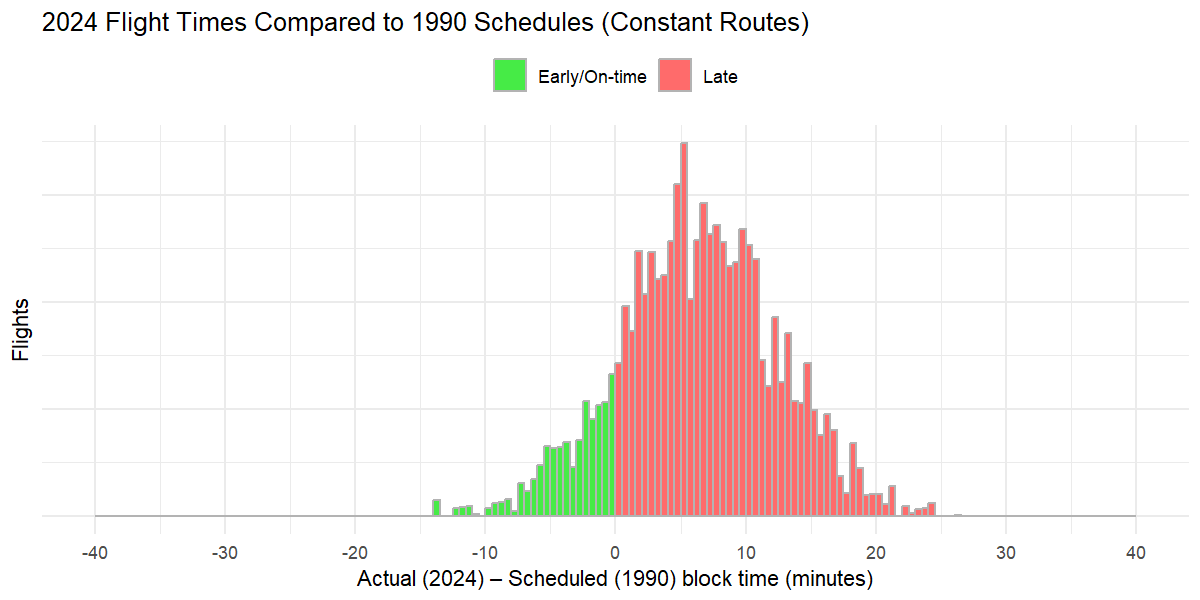

One way to measure delays is too look at the difference between the scheduled flight time and the actually realized flight time. If we look at the distribution of average delay across all routes in 1990, we get a graph that looks like this:

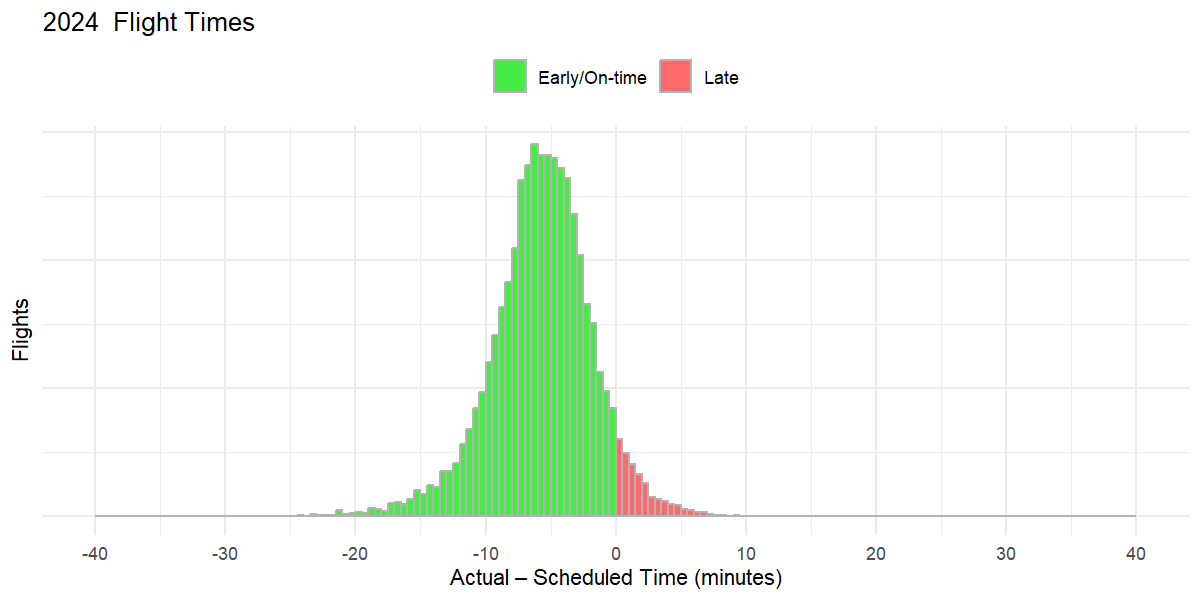

The average flight on most routes arrives right around their scheduled time, some are early, some are late, with a slight skew towards delays rather than early arrivals. So if delays are getting more common and/or longer then we should see this distribution shift to the right. Here’s what it looks like in 2024:

I claimed at the top that delays are getting more common, but this shows the exact opposite! Somehow, on ~85% of routes in 2024, the average flight was early! Before celebrating the well-oiled machinery of commercial aviation, we should practice some suspicion. Why, after all, wouldn’t the scheduled flight times update to match the actual most likely flight time? And why does it nonetheless seem like every other flight I’m on these days is late?

Here’s another perspective on this data. Instead of looking at the difference between actual and scheduled times, we can look at the total scheduled and realized flight times over the years.

. . .

Now we have some explanation for the pattern we saw above. Within the same routes, flights are now about 10 minutes longer than they were in 1987, partly reflecting more frequent delays pulling up average flight times and partly due to slower cruising speeds for fuel saving.

Starting around 2008, Scheduled flight times began increasing even faster than actual ones, and are now 20 minutes longer than their 1987 pairs along the same routes. This divergence makes it look like far more flights are early in 2024 when in reality almost all flights are taking longer.

Similarly, if take all the routes in the 2024 graph and compare the actual flight time to the scheduled flight time on that same route in 1990, we see that most flights in 2024 are late by 1990 standards.

The extra 10 minutes across all of these routes probably costs travelers something like $6 billion a year, but it doesn’t prove my claim at the start that long delays are becoming more likely. For that, we need to return to the difference between scheduled and actual times, despite the bias of rising scheduled flight times.

Diving into other areas covered in the initial post above, Tabarrok explores safety. In this area he concludes, “Overall, the safety record of air travel is stellar and still getting better.”

Regarding travelers’ explicit cost, “The inflection points in this price graph line up roughly with changes in the delay trends above. We are paying less and getting less.”

He offers some thoughts with evidence of what might be causing these frictions and reversals of the long-term improvement trend. In that section he provides an interesting point that:

All the major US airlines aren’t transportation companies at all. They are credit card companies with a couple of hangars attached. That’s according to new data from Ben Marrow at The Economist, showing the breakdown of profits across the different revenue streams of major American airlines.

. . .

The connection between this financialization of air travel to increasing delays is difficult to make explicit, but something about the coincidence of credit-card-mile loans shifting transportation into a loss-leader sector, airfare prices falling, and a rapid increase in the rate of long delays is too suggestive to ignore.

So yes, there is nuance to consider giving some credence to the reservations we may have about how joyous we should be upon making our next reservations [sorry, couldn’t resist].

As he concludes,

Recent anecdata about the quality of air travel has been universally negative, at least in my experience. Looking to the data, the overall picture is one of a service that is simultaneously safer, cheaper, and less reliable. Whether this nets out in air travel being worse than it was in the past is difficult to say, but it is clear that air travel could be much better than it is today.

My takeaway is to celebrate the gains, let go the false memory of a better yesterday, and strive/insist on further improvements. We haven’t ever done better, and we can do better yet.