Links - Threats to Our Success

The calls are coming from inside the house . . .

The United States is extremely wealthy and successful. This is true in an absolute sense today—as compared to any point in human history—and a relative sense—as compared to other countries currently. While the nation does face threats from abroad, though not as strongly as it once did, its biggest risk to further success probably comes from within.

Here are three examples along those lines. We start very topically with trade and the Trump administration’s quixotic quest to quelch our gains from trade. Always a wise sage on this topic, Don Boudreaux teams up with Phil Gramm in this Wall Street Journal piece (ungated here).

They make a succinct case that trade deficits are only mythically connected to economic growth. They offer very clear thinking on this topic that continues to baffle so many.

Has the expansion of global trade “hollowed out” U.S. manufacturing, as Joe Biden claimed in 2022? No. U.S. industrial production today is more than double what it was in 1975, the last time we ran a trade surplus. It’s 55% higher than in 1994, when the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect, and it’s 18% higher than it was when China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Real wages are up 19% from 1994 and 10% from 2001. The inflation-adjusted value of America’s capital stock is 36% higher today than it was in 2001, 66% higher than it was in 1994, and 178% higher than it was in 1975.

Manufacturing as a share of total nonfarm employment peaked during World War II and has declined ever since, following the pattern of employment in agriculture, which fell from 40% of the labor force to 2% over the course of the 20th century. This is attributable not to globalization, but to the spread of modern technology and the rise in demand for services relative to goods. Neither Nafta nor China’s membership in the WTO notably increased the secular rate of decline in the share of workers employed in manufacturing.

The poverty that is naturally, inextricably tied to the MAGA economic program is a dreadful threat to reverse so much progress that has been made.

There will be MUCH more to come on this topic in the near future as it is sadly not going away. Yesterday, April 2nd, was so-called “Liberation Day” where we were liberated from any economic sense.

Next we move to Dynomight doing a deep dive on if you have to get government’s permission to do independent research. The perhaps surprising and certainly frustrating answer is “likely so”.

This is an absolutely GREAT example of good intentions exploding into regulatory quagmires that halt progress. I knew IRBs were bad along many dimensions. I had no idea how pervasive and perverted they truly are.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “That can’t be right! The government can’t possibly claim to regulate what me and my roommates eat at home! That would be stupid!” Yes, it would be stupid. But who says the world makes sense?

Along the way I learned about INDs (Investigational New Drug)—something new for me to be totally astounded and flummoxed by. DOGE, where are you when we need you?

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “That can’t be right! That would mean that if I wanted to study if some normal food reduced the odds of, say, diabetes, then I wouldn’t just need IRB approval, I would also need to submit a freaking IND! That would be stupid!”

But the FDA is quite clear that this is right:

As is the case for a dietary supplement, a food is considered to be a drug if it is “intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease,” except that a food may bear an authorized health claim about reducing the risk of a disease without becoming a drug (see section VI.D.3). Therefore, a clinical investigation intended to evaluate the effect of a food on a disease would require an IND under part 312. For example, a clinical investigation intended to evaluate the effect of a food on the signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease would require an IND.

In his conclusion he makes a critically good point that alludes to a permissionless framework that has been proven time and again to be superior to this mother-may-I approach:

As an analogy, driving a car is dangerous. Whenever I drive, I could easily kill someone. But the government doesn’t force me to submit a driving plan any time I want to go somewhere. Instead, if I misbehave, I am punished in retrospect. Why don’t we apply the same policy to research?

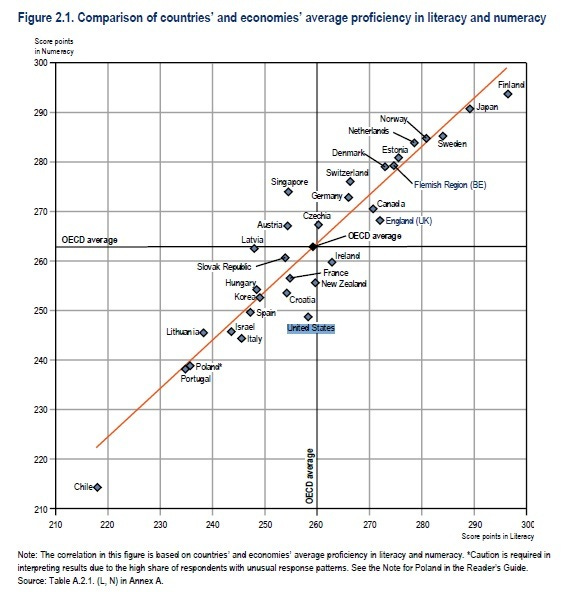

Finally, we continue to fail ourselves regarding education. Timothy Taylor reviews recent OECD survey results of adult skills.

These results are equally both stunning and concerning for the United States. It is all the more peculiar when you realize how much wealthier the United States is, and how much faster the United States has grown over the last two decades compared to these foreign rivals.

Beyond the average comparison lies a more disturbing truth. The within-country gap in the U.S. between the best and the worst performers is among the worst.

Perhaps more troubling is that within the US scores, the gap between the 90th and the 10th percentile is either widest, or close to widest, across countries. In other words, the US average score is made up of both exceptionally high-performing and low-performing scores.

For those who might reflexively think this is because we don’t prioritize education, I would say they are likely right in an unintentional way and wrong in their intended criticism. Considering the former where they are correct, we have a government-union-dominated system that works for the providers and bureaucrats at the expense of education—not to mention the failed conceptual framework it operates under.

Considering the latter where they are incorrect, spending in the U.S. matches or exceeds that of other nations often by large multiples. It is not a raw resources issue. It is a rotten system.

Where we might go but for our self-imposed limitations.