I.

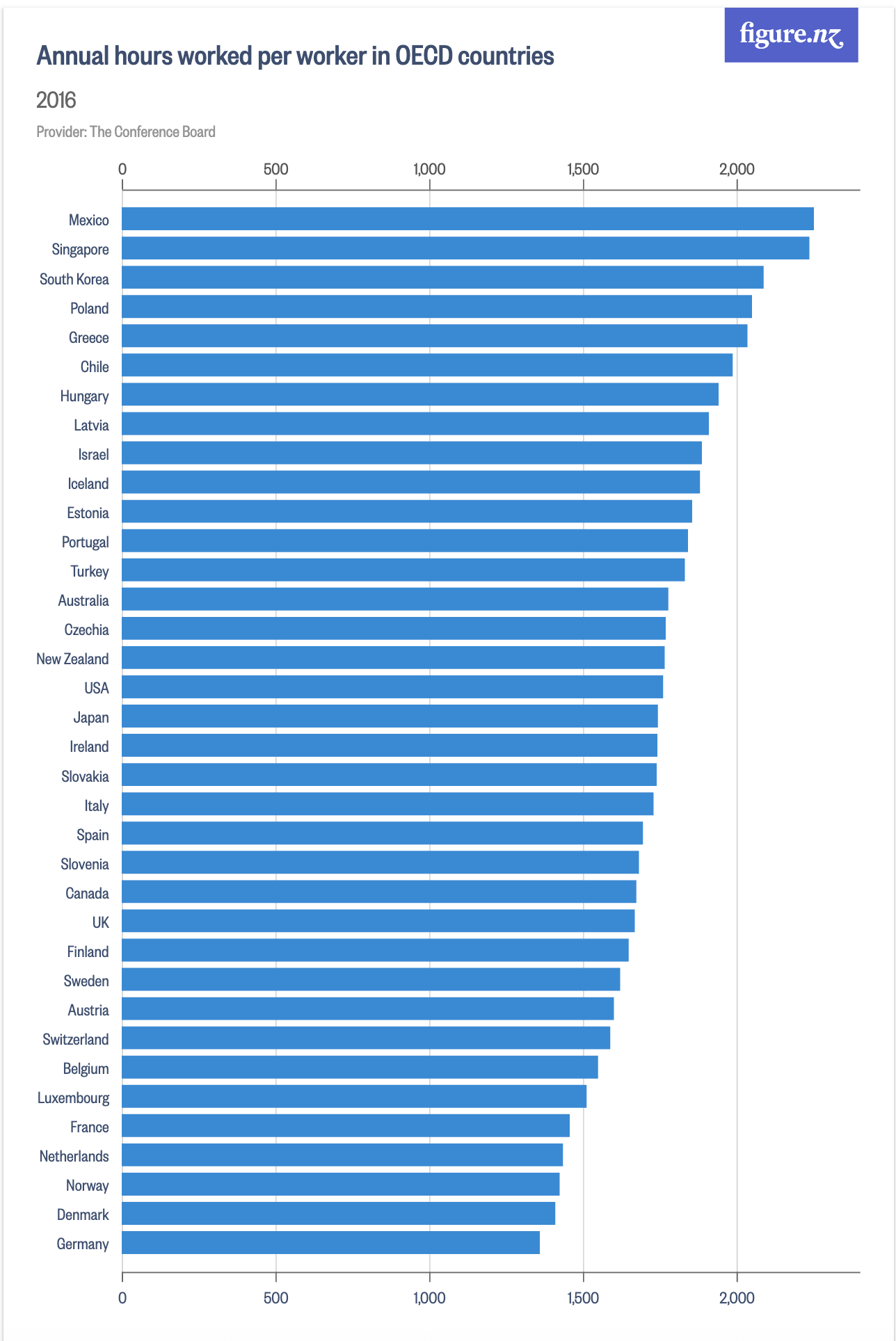

When it comes to work-ethic stereotypes, you simply don’t think of Germans as being on the low end. And yet . . .

Germans have perhaps the lowest level of annual hours worked in the entire world:

That is from Scott Sumner discussing if stereotypes are often true. He works through good examples of how and where our thinking goes awry with these generalizations and false comparisons.

Specifically on German workers he goes on to write:

So where did the hard-working German stereotype come from? Consider that Germany is a very affluent country with a highly productive workforce. In addition, Germans are often seen as being quite orderly and disciplined. Those presumably accurate stereotypes are often (correctly) associated with hard work. And perhaps during the 1360 hours that the average German is on the job, they do work very hard. Maybe they take fewer coffee breaks. Or perhaps they study harder when young, allowing them to become more productive and thus work fewer hours. But it is not true that Germans are hard working in the conventional sense of the term—working long hours.

II.

There is a lot about the labor market most people don’t understand. One thing in particular is how dynamic it is.

Start with the basic facts. The Business Dynamics Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau demonstrate that, in a typical recent year, about 10% of establishments will close and another 10% will open. The job-creation rate hovers around 15% of total employment. The job-destruction rate is similar. Every five years, roughly half of all jobs turn over.

That is from Brian Albrecht in a larger discussion of creative destruction and the recent economic Noble winners.

III.

One implication of the underappreciated dynamism of the labor market is to realize how important immigrants are to it. This would include how much immigrants help add lubrication to the process filling much needed roles and changing with those changing needs. Cato’s David Bier gives examples specific to just one particular group of immigrant workers, H-1B visa holders.

In fact, tens of thousands of H‑1B workers leave their original H‑1B employers every year. Figure 1 shows the number of H‑1B workers switching to new employers by fiscal year. Between fiscal year 2005 and 2024, H‑1B workers changed jobs over one million times (1,115,069). The number of switches grew from about 24,000 in 2005 to a record 123,888 in 2022—a more than fivefold increase. The number of approved H‑1B petitions for a change of employer has fallen in the past two years, plummeting to just 63,865 in 2024.

Keep in mind that this is within a pool of only about 700,000 H-1B workers. So that is A LOT of turnover.