Surprising Stats (Suboptimal Edition)

Did you know . . . ?

I.

If you’ve ever been to NYC, you’ve probably noticed the blocks and blocks of scaffolding and boarded up store fronts for businesses that are otherwise open. But you probably didn’t realize the extent to which this is happening, nor would you likely know the reasons why. Alex Tabarrok fills us in:

Local Law 11 requires owners of New York City’s 16,000-plus buildings over six stories to get a “close-up, hands-on” facade inspection every five years. Repair costs in NYC’s bureaucratic and labor-union driven system are very high, so the owners throw up “temporary” plywood sheds that often sit there for a decade. NYC now has some 400 miles of ugly sheds.

The ~9,000 sheds stretching nearly 400 miles have installation costs around $100–150 per linear foot and ongoing rents of about 5–6% of that per month, implying something like $150 million plus a year in shed rentals citywide.

There is goodish news here, but don’t get your hopes up. They aren’t reforming the law or looking for technology solutions to stop the back log. How silly of you to think that. No, fool, they are just going to pretty the sheds up so the wrapped appearance will be slightly improved as they let them linger.

II.

It is a shame that NYC allows itself to look like a zombie apocalypse. The reasonable question is could there be a better way.

Let’s consider something else that demands but doesn’t get proper questioning: medical testing. In particular PSA tests for middle-aged men.

The absolute rates of prostate cancer deaths were 1.4% vs 1.6% in the screened vs control arm. So the absolute risk reduction was 0.2%. This means that the number needed to screen to prevent one prostate cancer death is approximately 500. I like to think of this as: 499 out of 500 men get no benefit from being invited to be screened.

That is from Dr. John Mandrola writing at Sensible Medicine discussing a study that began in 1993 that now has a 23-year follow-up. This is an important challenge to the conventional wisdom that medical testing is benign and always desirable.

It is hard to get it into your head yet true that it is not always better to fight cancer risk by screening for it. The silence of not knowing is better when what you “know” is not actually helpful. That is the case with much of prostate cancer—it is not a common cause of deaths. Additionally, not all prostate cancers are worth the bombs of surgery and radiation. As Mandrola says, “The problem is that PSA tests cannot distinguish the slow-growing from aggressive forms.”

III.

Something that we can distinguish quite easily is how much homeownership is changing seemingly everyday.

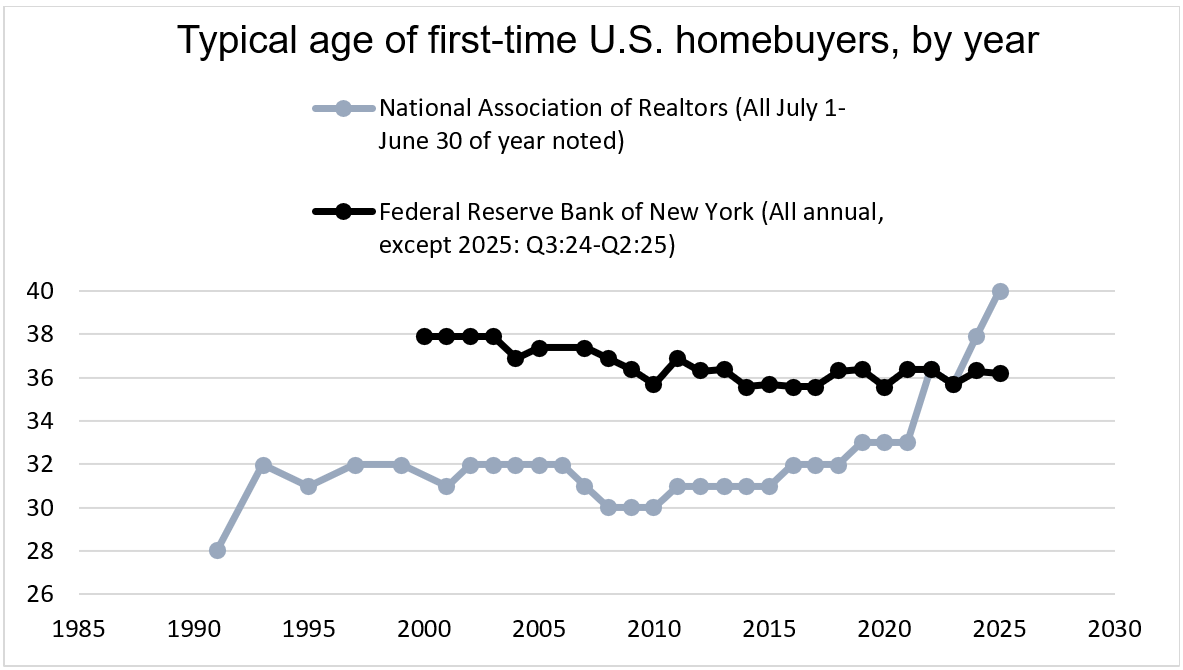

If owning a home is still the American dream, then it is increasingly out of reach for many young Americans. The average age of a first-time homebuyer is now 40, up from 33 just a few years ago and 29 in 1981.

That is from Allison Schrager writing at Bloomberg.

She makes the point that this is not altogether a bad thing writing,

To which I say: It’s just as well. Buying a home in your 20s is not the best financial goal, nor should it define the American dream of financial success.

Her point is well made. One thing she only alludes to is how homeownership ties one down geographically hindering one’s willingness and ability to relocate—an on-going problem of late.

While arguing that the increase in age isn’t necessarily a bad thing, she does address the substantial increases in housing unaffordability. These developments have become impossible to ignore, and she emphasizes the negative effects.

Channeling Kevin Erdmann, I believe he would raise the point that the disastrous policy choice made 15 years ago to make mortgages all but illegal for what was the main mortgage consumer is a factor to consider here. And the knock-on effects of that contribute strongly to driving rental costs up.

So I’m not as sanguine as Schrager on the increase in first-time buyer age. There is more to it than simply young people making (or having made for them) a better financial decision. The underlying cause is what is critical—not the obvious effect. It’s never quite as it seems.

[Updated 2025-12-9]: It seems the estimate of the average homebuyer was from a National Association of Realtors survey, which only had a response rate of about 3.5%. Upon further review, the statistic is not standing up to scrutiny. The New York Federal Reserve estimates that the age for first time homebuyers has been fairly steady if not slightly declining over the past decade. They put the figure at about 36 years of age (see graph below).

Of the change, the points made above remain. There is a housing problem that is having strong negative and distorting effects.