*When* Would You Run?

There is really no doubt you should--just a question of when.

Watch this video if you haven’t seen it already, and then answer the question in the post title:

Click here for the full story.

It is easy to laugh at people from afar, watching them do something that we’ve been told from the outside was a mistake. But was it foolish? And more importantly, not would you have run but when would you run.

I would argue that the more foolish position would be to stay in one’s seat despite clear and growing indications that there was a reason to be moving quickly from the area.

Imagine if you were a tourist in Brazil for the first time. How would this change your perspective? Imagine that you had been in any number of frightening, flight-or-fight situations where RUN NOW is the appropriate response?

This is true before we layer on the fact that some people mistakenly shouted that it was a “police sweep” or considerations for how joining the crowd is the wise move from just a social desirability bias standpoint. I’m not claiming you should run because you want to fit in. I am claiming that running is the rational response for all but the very first few people, and even they may have an out depending on their specific vantage point.

One of the ongoing themes in cautionary tales both in general and specifically Tim Harford’s excellent series is that those who wait and see tend to be among the victims. For a specific example, consider the Fire at The Beverly Hills Supper Club.

Sometimes “Don’t just do something, STAND there!” is the correct, rational response. But crucially at other times the emotional, gut reaction, “Don’t just stand there, DO something!” is the best course of action. But how do we know when which is appropriate?

Specifically to the type of situation in both the Brazilian bar and the Supper Club fire, when do you look to the crowd for advice? Wisdom of the crowd versus foolish herding mentality.

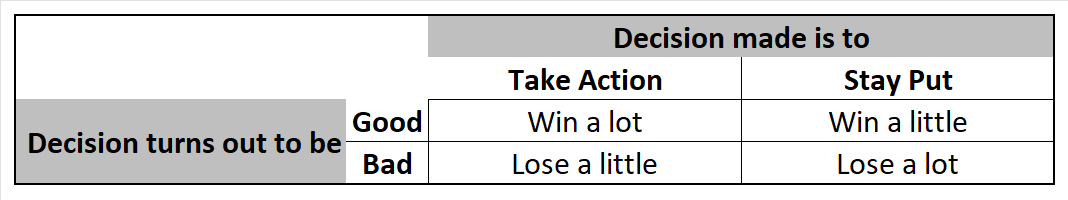

The easiest and perhaps sufficient rule to follow is a simple cost/cost analysis. How bad is it if I fail to act and that is a bad decision versus if I do act and that is a bad decision?

The next level would be a simple cost/benefit analysis. What is the net benefit-cost of each and then compare the two. For those who like to see things in a chart:

Still a next level would be to assign probabilities to each potential outcome (making sure they sum to 100%, of course). Yet that is probably too academic for all but those actually doing this academically. One, we are talking about situations where time is of the essence. Two, these would have to be drastically disparate probabilities to overcome the inherent differences (e.g., win a lot versus lose a little).

A different approach altogether would be to ask the following questions:

Who might have important information I don’t have?

How are they acting?

Is the prudent option the costlier option?

If so and people are taking it anyway, this is a strong reason to follow suit.

If so and people are not taking it, discount the crowd’s behavior.

If not and people are taking it, discount the crowd’s behavior.

If not and people are not taking it, this is a strong reason to follow suit.

Which option would I regret the most? Do the opposite!

That last question might be all that is needed for fight-or-flight decisions. All that is left is to have a clear understanding of what is and what is not a fight-or-flight decision.

We almost never face a fight-or-flight decision in the following realms although it often seems like we do: investing, politics, big purchases like car buying, dating, et al.

We often do face fight-or-flight decisions in realms that are at least two of the following: unfamiliar, volatile, hostile, heightened danger, minimal option (e.g., for escape), and asymmetrical (e.g., power imbalance or bad risk/reward tradeoff).

Proceed with caution, and know that caution might including running for your life and looking dumb (but alive) after.