Do-It-Yourself Ruination

Go broke with just this one, simple trick.

Imagine you are a general practitioner specializing in family practice. One day a father whose family you’ve treated for years comes in with his son. The son is suffering from dull belly pain that has become sharp. He has a fever and is nauseous.

Upon examination you confirm your initial suspicions that he is very likely suffering an appendicitis. You immediately recommend him to see a specialist who most likely will recommend surgery.

The father then looks at you with incredulity and says, “A surgeon? You’re a doctor. What do I need a specialist for? Why can’t you do this?”

Even worse would be the father who upon hearing this diagnosis then decided to go home and with the help of Dr. Internet, AI, and some home equipment perform the surgery himself.

As obviously dumb as this hypothetical father is acting, it wasn’t always so dumb to think this way. And in other areas of life we find people still making these same choices albeit in situations with lower stakes.

Consider investing and portfolio management, and before you think I’m about to pick on individual investors as being like the father in our story above, I’m largely not going to. My focus primarily will be on the family practice MD who unlike our doctor above will overstep his abilities and be our culprit.

Yes, at the extremes the analogy breaks down. Portfolio management is not as high-skilled as surgery nor is it life-and-death risk, but reckless investing can have devastating consequences. It can bring financial ruin.

It is said that a poor carpenter blames his tools. It should also be said that a poor carpenter should not be trusted with the powerful tools only an expert professional can successfully use.

Consider the otherwise laudable development of low-cost, low-friction investing. Robinhood is both a great-American success story as well as a cautionary tale all at once.

This is really just investment democratization 2.0 where 1.0 was discount brokerage in the late 1990s. To be more accurate those are just two large leaps in an ever-improving world of greater access to better investing resources. The first discounted brokers (1970s), index funds, and ETFs are among the many innovations that have brought both capabilities and consequences for ever-more average investors.

The tools Robinhood has enabled is setting up a few people for financial triumph and a lot of people for financial destruction. And I am not just thinking about the customers. Another thing entirely can be said about Robinhood itself as it profits and perhaps exploits an unsophisticated customer base.

I am not going to break with my principles and say that these activities or products should be more heavily regulated much less prohibited. But I will recognize the elephant in the libertarian-dream room that is the unfortunate consequences that inevitably occur when people are given abilities without the requisite self-imposed responsibility. People must be allowed to make mistakes in order for us to have freedom or achieve economic growth. I believe this is the balance we must tolerate.

Yet my primary criticism is not the mistakes of the less-than-ordinary but all-too-typical investor. My criticism is on investment professionals who go about playing a game they have no reason to believe they can win. And doing so with other people’s money.

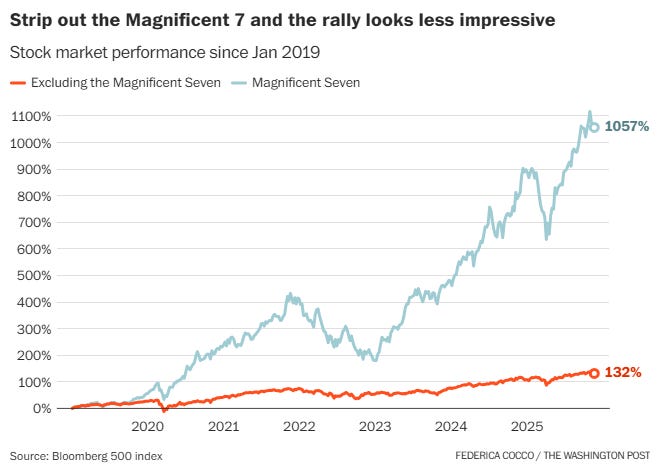

This article with the following chart from this Washington Post article has been making the rounds:

Anyone who has enjoyed the ride that has been the light-blue line has been extremely lucky. Not just fortunate, but lucky. Lucky in the dumb-luck sense. It is not a track record I would want to tout had I personally achieved it because I know too much to know how dumb it would make me look—to an astute observer at least. Of course, I might dry those embarrassed eyes with my $100 bills . . .

And as an investment professional, if I were to have achieved this track record for my clients, I should be accused of malpractice in the vast majority of cases.

As a strong rule, allowing a portfolio to have this kind of concentration risk would be beyond imprudent. Where there might exist extreme hypothetical cases that test this rule, exploring them makes the point. Even for a young, healthy, well-employed person who stands likely to inherit a small fortune, having all of their current financial assets in just seven stocks in largely the same market and industry is not advisable.

Before you invoke the “but what about Warren Buffett” objection and before I counter with the “so you think you’re the next Warren Buffett?” defense, consider that a Buffett, someone winning the game in the long run, is inevitable. More importantly, Buffett (and Munger) were superhumans at this who also . . . [whispers] . . . had the benefit of access to very cheap, long-duration capital. Give me a crack at it with 30+ years of low-interest financing. Slight leverage over a long span of investing in great compounders is great work if you can get it.

Set aside the one-in-one-hundred-million investors like Buffett and Munger. Most sophisticated and responsible investors and investment managers are operating in the realm that won’t allow them to reach the stars and, by extension, prevent them from crashing permanently to the ground. This is where the analogy returns.

Most of us as either individuals or portfolio managers for others are the general practitioner in our story above. We know enough to know we can’t possibly know enough to pick individual stocks much less concentrate portfolios in them. Where they are needed/desired, we hire specialists (the surgeon in the analogy) who we can somewhat freeride upon.

The specialists are active managers engaged in stock or bond picking. They work at places that sell things like mutual funds. We get to hire (buy) them as we wish and fire (sell) them the same. That’s where the freeride comes in. In the bad cases we might lose a lot with what we place under their care, but it will just be a portion of our investment. Their failure is very partial for us but perhaps complete for them—fail enough and they lose their jobs along with their reputations.

So, sensibly we hire the specialists to take the big risks.

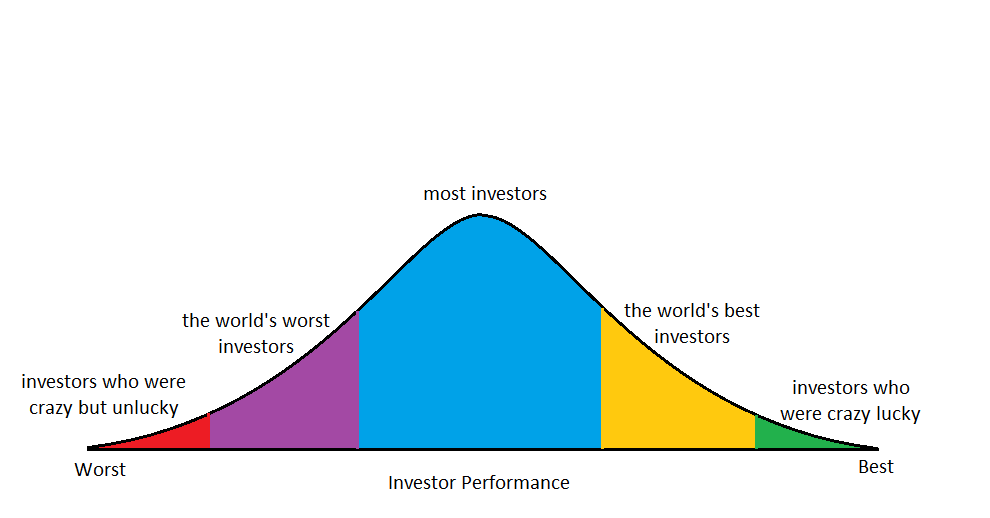

Consider this stylized distribution of investor performance:

Where do you want to be in this chart? Be careful how you answer not just because I am judging you. More importantly you are judging you. That is to say, your future self will cast “shame, shame, shame, shame on you” if you try to win the dance contest by being at the far right end of the graph.

Here is what I mean. Responsible investors and portfolio managers are not trying to get into the green section because they know that is the fastest, surest route to the red section. Even those stock-picking specialists we seek to hire have both prudent and selfish reasons to avoid such aims.1

You may be confused by my labeling so let me explain.

The crazy but unlucky group doesn’t get the label “world’s worst investors” because they weren’t really investors. They were gamblers playing Russian roulette. To call them investors is an insult to the people in the purple, blue, and gold sections who were actually out there reasonably trying. The red section is worst than the worst.

Similarly the green section is reserved for “investors” who were really just gamblers who happened to win. Benchmarking ourselves against either extreme is not reasonable. Hopefully you are not taking the kind of risk that can land you in the red or green realms.

And this is a snapshot of what the distribution looks like. If done as a time-series depiction the distribution would stop being normal (a so-called bell curve). The lumpiness at the lower (red) extreme would grow as it filled with those departing the green section without replacement. Stay long enough at the casino, and you’ll learn about this effect. You don’t eventually defeat the house by playing the slot machine endlessly. You eventually go broke as the payback is ALWAYS less than 100%. The casino counts on this as a way to eventually get the best of you. A slot machine with a 95% payback will give you back $.95 for every dollar you put in it. On average after the first dollar, it will give you back about $.90 on that returned 95 cents. Next you’ll have about 86 cents from the 90. Rinse and repeat until zero.

The market isn’t an entity intentionally set up to get you, but the implications of efficient markets effectively do the same thing. Over medium-long periods of time (like just 10 years), almost all the specialists fail to beat the market. The failure rate approaches 90% for those trying to do so against the S&P 500.

Thinking back to the WaPo chart above, investors whose portfolio entirely or mostly tracks the Mag 7’s rise over that time span are members of the green section in my distribution. For every one of them there is someone in the red section—a silent graveyard of investor Icaruses. Over time there will be many in the red for every one in the green—mostly populated by former green section members who were renting not owning their position.

So my advice to individual investors is really the same as for professional portfolio managers working for individual investors: be the general practitioner. Don’t try to play a certainly eventually losing game. Replace your FOMO with PIMO (Pride In Missing Out).

The principle-agent problem I’m alluding to is beyond the scope of this post—the idea that the specialists aren’t taking enough risk (concentration and otherwise). Just know that it is an important second-order concern for us as investors.

I may not always engage publicly , but I read every post delivered to my inbox. I wanted to take a moment to appreciate the effort and honesty you put into your writing. Your insights are consistently articulate/engaging, and I find myself aligning with your perspective more often than not. Really excellent work.