Football Analyzed as a Strong-Link/Weak-Link Problem

A framework for understanding what kind of game your a playing applied to football specifically as an example

Adam Mastroianni writing at the Substack Experimental History recently examined the difference between strong-link and weak-link problems (HT: Maxwell Tabarrok). The essence of the concept is that success in some realms depends on maximizing the weakest link regardless of how strong the strongest is while in others success depends on maximizing the strongest link regardless of how weak the weakest link is.

He applies the concept to science arguing that for the most part it is a strong-link problem. He first heard about the concept listening to Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast Revisionist History, which means I heard about it then too but had since forgotten about it. In the episode they are discussing the Chris Anderson book The Numbers Game. Its subtitle is “Why Everything You Know About Soccer Is Wrong”.

I love this concept. It would make for a marvelous deep-dive in a future post. There are so many interesting places to apply this framework1. But for today I will do a minor version applying the concept to American football.

In the book Anderson argues that soccer is a weak-link game. I would argue the same is true for American football. At least in large part this seems to be the case, but it doesn’t always hold. Let’s examine.

Here are the ways in which football exhibits a strong-link problem:

Conference and national champions - determining champions among all teams

Plays that succeed from a single player or couple of players’ individual success - big plays

Player positions and position groups - determining who is the best 11 on each side of the ball

Offense for the most part

Here are the ways in which football exhibits a weak-link problem:

Season outcomes - each team’s individual win/loss record

Game outcomes - who wins a particular game

Plays that break down because of one player’s huge mistake - busts

Play of the unit on the field - performance of the best/starting/active 11 on each side

Defense for the most part

The old adage defense wins championships might be on to something after all. Some team is going to be a champion—that is pure strong-link. But for any particular team to have a chance to be the champion, they must solve a weak-link problem.

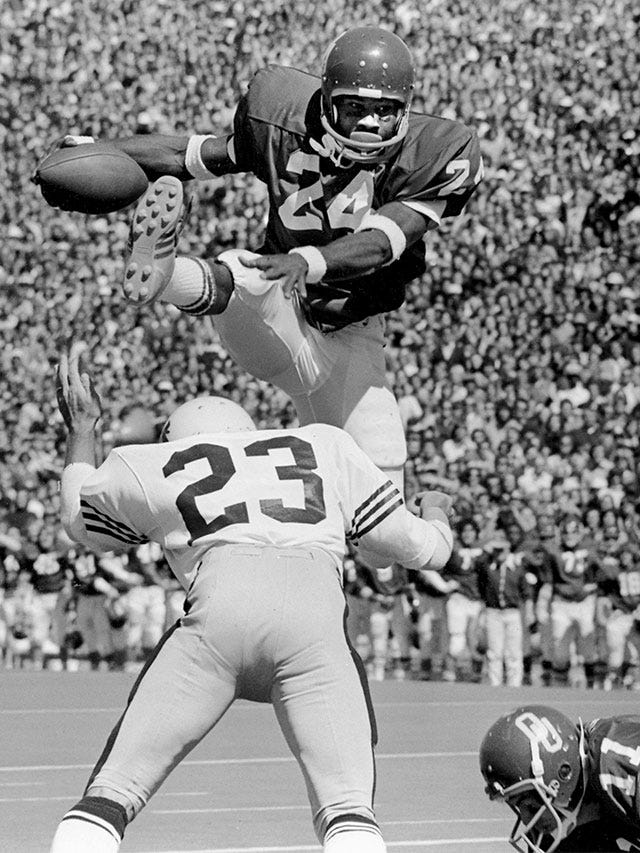

Notice other interactions. Big plays are going to be when a single player stands out or exploits a mistake known as a bust (e.g., linebacker jumps the pass and offensive lineman fails to block, quarterback and receiver hook up, star running back slips through the defense like smoke through a keyhole, etc.). The ability to have a big play is a strong-link problem, but it might coincide with a bust, a weak-link problem.

Figuring out who should be the starter at each position is by itself a strong-link problem in that a backup who doesn’t see the field does not noticeably impact the game no matter how good or bad he is relative to the starter. Yet the depth chart in its entirety is a weak-link problem as that will determine the group’s performance play in and play out throughout a game and season. Here again the backups will matter as they (1) might end up playing meaningful roles if not replacement roles for injured starters, (2) are needed in practice as starters themselves, and (3) will hopefully develop to become potential starters in the future. Thus, determining who plays generally gravitates to be a weak-link problem even though each component of solving that problem is strong link in nature.

While it is true that a team’s performance on offense will tend to exhibit as a weak-link problem throughout the course of a full game and season, it is much easier for an offense to overcome a weak link than it is for defense. A defense with a weak link can be easily exploited. An offense must only work around the weakness, which it can do as it is generally dictating the type (run/pass), direction (left/middle/right), and style of play (quick passes/deep threat/run-pass option).

Competitive balance is always an interesting if not fraught topic in sports. This is an area dear to my mind as it was the subject on which I have published research. So-called parity is most certainly a weak-link problem. So much so, it is partially solved by preventing solutions to strong-link problems—that is to say, by restricting how good the best can become.

In certain less popular sports we tend to see strong dominance by elite teams/athletes. College softball, women’s college basketball, Olympic hockey, Olympic women’s soccer, Olympic basketball (until recently), table tennis, etc. all have strong concentration at the top. Arguably this domination of a strong-link solution meaningfully lessens the fan draw which in turn exacerbates the problem—a kind of local maximum problem as pursuit of weak-link solutions are nearly extinguished. In other words in these extreme cases the dominance of particular teams harms the popularity and limits the success of these sports.

At the other end of the spectrum lie sports with so much competitive balance that anyone can win and therefore nobody really cares much. In the extreme every outcome would be a coin flip—basically random. There aren’t great examples of this at an amateur much less professional level for obvious reasons—these sports fail to launch or quickly die out. At less of an extreme one can find many examples of a sport suffering when competitive balance rises above a certain threshold—too much competitive balance causes the sport to wane. The NBA might be an example more or less over the past decade. Perhaps this explains some of baseball’s steady decline (who knew we needed the Yankees to be a dynasty).2

Back to football, one of the underlying factors in a head coach’s success will be his ability to appropriately manage to the problem type he is facing. Whether it is explicitly understood or not, the formula for having a great offense is very different than it is for a great defense. Perhaps this is why and how Lincoln Riley (great offense/poor defense) and Kirk Ferentz (poor offense/great defense) both have been limited in their overall success. It is not enough to be excellent on one side of the ball. Elite coaching requires greatness on both.

Considering what type of problem one is facing—whether it is more of a weak-link or strong-link problem—is a key method for finding long-term equilibrium as well as success.

One example would be in economics thinking about inequality—a woefully misguided worry. Along those lines I would argue that Marxism along with its derivatives (socialism, communism, fascism, et al.) fails in large part because it is attempting to solve a strong-link problem by applying a weak-link solution.

Admittedly highly speculative.