I'm Theft Proof

My wealth (personal and social) by itself is actually my protection.

You may have heard the term judgment proof when referring to someone so destitute that you basically can’t get any kind of meaningful legal judgment against them. In that case, the person could rightly be viewed as very dangerous since they can’t pay for any liability they may generate.

Borrowing from that idea, I’d like to introduce a similar concept: theft proof. To explain, I’ll show how I think this applies to me.

By any reasonable measure, I am extremely wealthy. I’m easily in the upper 1% of 1% of all of human history and, as I’ve shown before, wealthier than John D. Rockefeller. Yet I’m only barely above middle class in the U.S. Historically being even at the low end of the high end of wealth (as I am currently) meant being at high risk for crime.

Yet, I am basically immune to theft. Well, that’s an exaggeration, but there is a good deal of truth to it worth exploring.

There are two reasons why I am largely theft proof:

One, I am wealthy enough that satisfying my needs and desires in terms of physical things does not come with big sacrifices. I can replace what is lost fairly easily. This is the minor reason.

Two, I live in America, the wealthiest society there’s ever been. Thus, the stuff I own is not stuff that would be very desirable for a thief to steal. Not because it is not nice but because good stuff is cheap. This means that the things I have that might be worth stealing if I were in a poor economy are generally not worth the effort to steal in this one. This is the major reason.

No one is going to take my furniture, rugs, and lamps. Somebody might take my televisions, but that would just be a mere inconvenience as the new TVs I would buy would be better than the ones I was losing. Clothing? Nobody wants my clothes—most of the time not even me. Even if I had designer towels and delicate China sets, you aren’t going to get much fencing them on the black market. There is a reason you don’t hear about smash-n-grabs at Williams Sonoma. Relatively expensive pots and pans and flatware have low conversion value—a set of steak knives is not first prize.

They could get my computers and iPad among other such devices. If they hunted long enough, they might find a little bit of cash. After that, they’re going to come up well short of a worthwhile trip—definitely not worth the criminal risk.1

To be fair, I am probably unique in my cohort in that I don’t have a lot of items desirable to a thief. I have less things like jewelry and watches, guns, valuable art and precious metals, or expensive tools and fancy cars in the garage than others like me. Yet even the most extravagant of folks like myself have fairly limited risk since they live in a wealthy society.

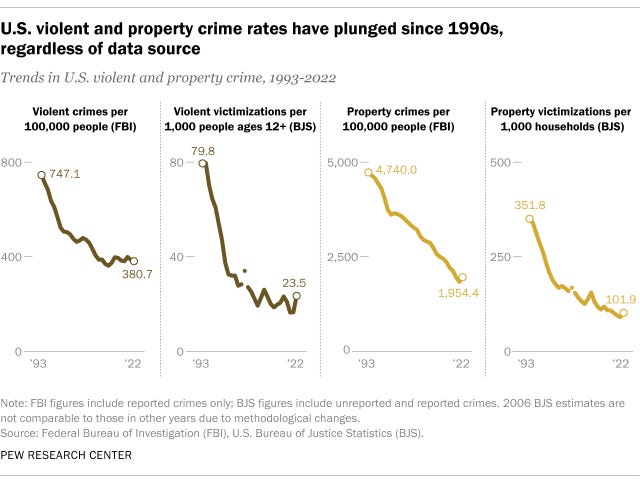

I’m not denying that robbery and burglary still exist, but they are very much smaller factors today. Despite the brief increase post Covid, they’ve been on a steady long-term decline. It is my contention that a big reason why is because we are simply a lot richer than we were in the past.

The loss from being a victim of a property crime would still be very real from an emotional sense—the feeling of being violated. Additionally, the risk to me of vandalism is fairly high especially relative to theft risk since I have a lot more to lose than a thief has to gain.

Importantly, there is an unlikely risk of an electronic theft of my financial accounts. This would take a sophisticated attack. Even in these cases I likely would not be the liable party to bear the loss entirely, and I have insurance against theft. In contrast hacking my computer files to delete or alter them by itself would just be an act of vandalism—something, again, I am more at risk for. And I have backups, of course.

While my insurance policies would cover my losses from theft, this is just one step removed from me covering it myself. I have reached a level of wealth that allows me to afford insurance against losses including theft. This is partially due to living in a society wealthy enough and extensive enough to provide such insurance.

Perhaps this is just a post about abundance and how lucky I am to be on this side of it. I fully realize that I am well above average in income and net worth while still being well below many “above” me. But my own wealth is not enough to explain this lack of theft risk. Back to the point raised at the top, being rich did not historically make one immune to theft.

So I want to emphasize that I believe the dominant role here is being played by my society growing sufficiently richer rather than me myself getting richer. The relatively wealthy in places like Haiti have a lot to lose from theft alone—their ability to get back to where they are if they were a victim of theft is very limited. This cannot be a surprise. For most of human history including the “civilized” period of enlightenment Europe everyone was a constant robbery target. Today almost all people in developing economies are still on the wrong side of theft risk. It is higher for those at the lowest end but still prevalent for basically all people short of the ultra rich and the politically powerful including authoritarian strongmen.2

Once a threshold is passed, something fundamental changes. Wealth in a wealthy country like the U.S. buys you insulation from theft rather than exposure to it. More importantly simply living in a wealthy country insulates you from theft for all but the most vulnerable members. As wealth grows and spreads (even if unevenly, which is inevitable, but still extensively, which is also inevitable in a free market economy) the cost/benefit of theft grows ever less favorable. In that beneficial growth world the needs of those who might steal are more easily met through legitimate means. Simply put: As stuff gets less expensive, stealing stuff gets less appealing.

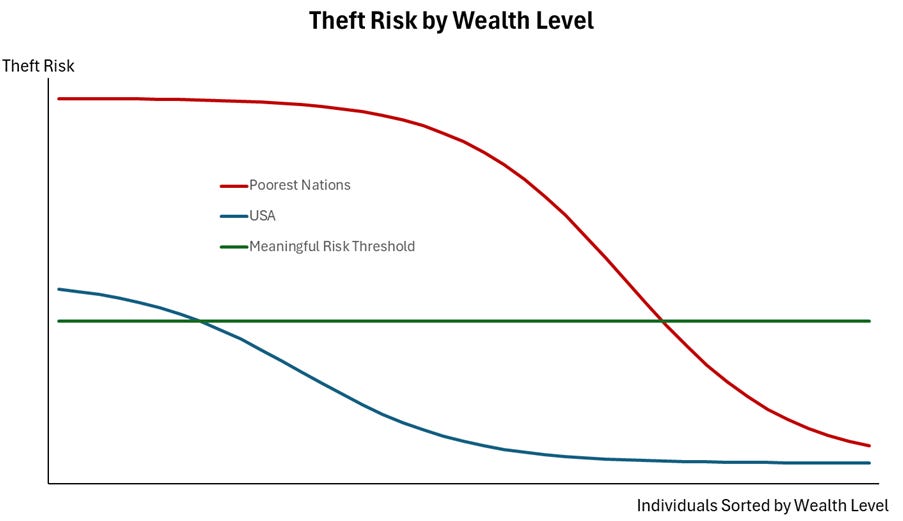

Maybe the risk level for people in various countries looks something like this:

As people get richer, their risk of theft declines slowly at first and then more rapidly and then at a decreasing rate. At some point it is below the threshold of being meaningful. For those in the wealthiest societies, this come fast. For those in the poorest, very slowly if at all.

Yes, there are still many (too many) in even the wealthiest societies who face theft risk as their own poverty condition cannot yet be overcome. With all of its flaws, public assistance works against this since as long as a poor person can still get government assistance, they can maintain a minimum consumption level. Private charities play an essential role here too. Still, not everyone is below the threshold yet. And they might not ever be as there is another interesting implication to this theory.

I’ve speculated before how our high violence and crime in the U.S. might actually be a cause of our high growth rates (or at least be connected to them). The hypothesis there was that growth was a compensatory factor for violence and crime.

Now I’d like to reverse it to speculate that causation might go in both directions. Here the hypothesis is that our wealth allows for a lot of property crimes, which might have knock-on effects leading to violent crime.

In a sense most all Americans are theft proof. American businesses are for sure below the level of meaningfulness. In both cases this allows/forces a high level of theft tolerance. Like inequality and pollution (Kuznets curve), it might be a cost we have to endure at least temporarily as we grow wealthier.

Eventually, we start to value safety and serenity highly enough that we again crack down on theft but more as a good unto itself rather than as a cost to avoid. When you are poor, you have to fight against theft for your survival. When you are less poor or somewhat rich, you can afford theft and diminishing returns means you cannot cost effectively fight it at the margin. When you are extraordinarily rich, you can afford to stamp it out in almost all regards.

PS: It occurs to me that the curves actually should start sloping upward for the poorest since a lack of stuff it itself a (perverse) protection against theft and because of the points made above regarding public assistance and private charity. Welfare cliffs are real and painful.

PPS: [in response during a conversation with a reader who expected the post to go in a different direction] I agree that one can escape the risk of ruination from theft through relative frugality (avoiding the risk by not being materialistic—spending so much that you DO have a lot to lose that cannot be replaced) and also by choosing to value that which cannot be stolen valuing people and experience over possessions (avoiding the psychological, emotional hurt and violation—you cannot take from me that which I have already enjoyed).

Yes, they very likely wouldn’t know that, although smart thieves do a good job sizing up their targets.

I’ll leave it to the reader to consider how this group (politically power and especially tyrants) should be themselves considered the thieves.