Reality-Based Investing

What you want should be framed by what you can get.

As investors, we have to take the world as it is rather than as we would prefer it to be. There are many angles to this. One I encounter regularly is a reconciliation between concerns about government debt and implications for the holders of that debt along with other financial assets.

Government is big, intrusive, and overbearing. It is a very expensive luxury that we are forcing upon ourselves. As a result, we have growing debt and needlessly burdensome regulations.

This puts a downward trajectory on economic growth and, hence, returns to capital investment. There are other factors like this for us to consider. Population growth is declining everywhere at a rapid and concerning pace. This is another very dire drag on economic growth.1

These factors alone imply expected returns for taking risk at all levels will be lower if not substantially lower than they otherwise would be. Hence, there is context for which we should frame our expectations about returns to capital.

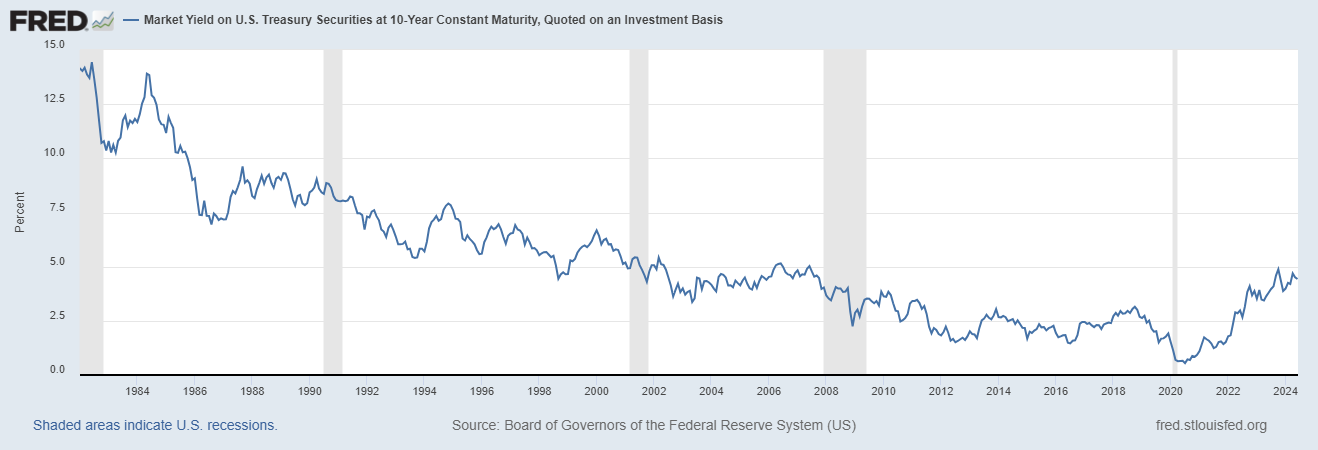

While interest rates on sovereign debt look more attractive today than they have in the recent past, they are themselves pricing risk. Part of this is inflation risk/expectations. Another part is default risk—perhaps the other side of the same coin.

A nominal 4.5% US government bond today is probably not the same as a 4.5% US government bond was in 2004 (20-large-deficit-years ago) even though the inflation-adjusted (real yield) for a 10-year UST was about 2% then as it is today, and we're talking nominally2 about the same underlying borrower—the U.S. government.

Yet, the bond today looks good as compared to alternatives in equities relative to that difference in 2004. Then the expected real return on stocks was about 5% whereas today it is about 3.6%. You can get a 5% expected real return today, but you will pay for it in terms of much higher risk. TANSTAAFL strikes again. If you don’t think that difference sounds significant, consider that it is the difference between doubling your money in about 14 years versus waiting about 20—a delay in time greater than 42%. Imagine having to delay retirement 6 years or settling for about 34% less to live on in retirement.

Equity valuations have gotten very high, which necessarily pushes down their expected returns. To the degree economic growth rates are constrained by the factors mention above (excessive government spending and regulation along with declining population growth rates) equity expected returns would further be restrained.

So U.S. government bonds when compared to stocks look better today than they usually have historically for a couple of reasons. The expected return for stocks has been pushed lower than it would be otherwise and bonds are riskier than they would be otherwise.

Environments where you can do better in safe bonds than stocks are not panaceas for investors. Rather they are low-return predicaments where investors have to settle for less and/or accept higher risk.

The capital markets don’t care what you need or want in terms of desired return. The capital markets only give us what we realistically can expect given the reality of the world as it is.

SOURCES:

To be sure not all trends and factors are negative. The world is generally getting more open, free, and connected—doomsaying, anti-globalists be damned! This is leading to a more developed world economically and a more peaceful world generally. As a result there may be underappreciated increasing returns to scale that will flow over into higher returns to capital.

But in a different sense.